Then I imagine a tiny drop splashing on to Thales of Miletus, the philosopher’s hand…the very drop that might have been inside my coffee this morning or perhaps inside yours, connecting us all beyond the borders of time, geography and identity.

p 489, note to reader

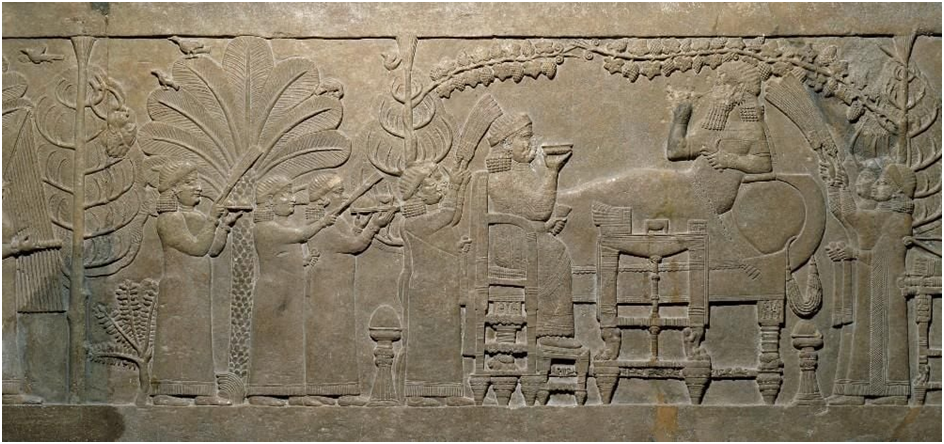

People may be familiar with the striking lion hunting friezes in the British Museum of the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, who ruled over a rich empire 640 years BCE. It was a civilisation light years ahead of what existed in Britain then. It is between the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates that human development really took off – writing, mathematics, the wheel, astronomy, road networks, chariots and more.

Shafak starts the novel here in the city of Nineveh which was later destroyed and erased from the map. A single raindrop falls on the King’s head. The water cycle has always existed and will continue if life survives on our planet. So it is theoretically possible for this single raindrop or molecules of it to fall on the heads of the other 19th century or 21st century characters in the book. This material possibility and the sense of humankind’s universal reliance on the water cycle allows Shafak to weave her web of interlocking stories across time and space so that everything finally converges

Three linked stories

Each story could form a novel on its own

- Arthur the unschooled 19th centrury autistic savant genius who deciphers the Assyrian language on the thousand of clay tablets in the British museum

- Narin, a Yazidi young girl who learns her communty’s millennial history and practical knowledge from her grandmother but then has to flee the Isis led genocide

- Zaleekhah, a contemporary hydrologist in London dealing with a broken marriage and her scientific research about the the water cycle and how its disruption by climate change will affect us all

On one level it is a literary contrivance, but it is built around a profound, materialist understanding of our relationship to nature. The coincidences and links make sense. The epic Poem of Gilgamesh provides another way in which the three stories are blended . The opening sequence shows how King Ashurbanipal has learnt the Poem of Gilgamesh. It is one of the oldest stories in world history.

Arthur, who ends up working in the British Museum because of his natural ability to unlock the Assyrian symbols, dedicates his life to finding the tablets with the missing verses of the poem. He travels to Mesopotamia and meets the great grandmother of Narin. Zaleekhah is also fascinated with the culture of the area and becomes friendly with a woman tattooist who specialises in using the ancient Assyrian language and shares her love of the Gilgamesh epic. The denouement unites the narratives.

Grounded in real events and people

You need a lot of meticulous, rigorous research to produce a book like this. Shafak recreates the sounds, smells and poverty of Victorian London, the fauna, flora and communities of Mesopotamia and the terror of Isis genocide against the Yazidi people.

She interweaves her fiction with a scaffolding of historical figures and events. For example there was an unschooled genius called George Smith who deciphered the clay tablets at the British Museum. The printing company where Arthur works did end up publishing Charles Dickens and we are aware of the barbaric acts of Isis against what they considered to be the devil worshiping Yazidi people.

Shafak was born in France but later lived with her parents in Ankara Turkey. Since 2019 she has been in self-imposed exile because of fear of prosecution by the repressive Erdogan regime. She wrote in 2016 in the New Yorker magazine:

Wave after wave of nationalism, isolationism, and tribalism have hit the shores of countries across Europe, and they have reached the United States. Jingoism and xenophobia are on the rise. It is an Age of Angst—and it is a short step from angst to anger and from anger to aggression. Wikipedia

A progressive novelist

The themes in her 13 novels are feminist, anti-colonial and ecological. She has come out as bisexual and her writing is sensitive to gender and sexual relations. This book deals with all this and specifically interrogates how the colonial world has appropriated the cultural artefacts of colonised communities. These themes emerge from her poetic, magical and insightful story telling. Narin’s grandmother in the story rescues and revitalises the wisdom of Yazidi culture.

One of the grandmother’s explanations of how Yazidis understand time and history makes one think of Gramsci’s famous quote about transitions:

There are cycles in nature, cycles in history.We call them dewr. Between the end of an era and the beginning of a new one there always a period of confusion, and those are the hardest times, may God help us. P 219

The late Marxist writer, Daniel Bensaid, wrote a brilliant treatise on the different cycles of time in Marxist theory – the political and economic have different rhythms and intersections. This book shows this in a literary way.

Rivers function as another character in the book. Shafak writes in English and like many second language writers (e.g. Conrad) this give a clarity and directness to her prose:

Rivers are fluid bridges – channels of communication between separate worlds. They link one bank to the other, the past to the future, the spring to the delta, earthlings to celestial beings, the visible to the invisible, and ultimately, the living to the dead They carry the spirits of the departed into the netherworld, and occasionally bring them back. In the sweeping currents and tidal pools shelter the secrets of foregone ages. The ripples on the surface of water are the scars of a river. There are wounds in its shadowy depths that even time cannot heal.

Remember the Yazidi genocide

Many Yazidis fleeing Isis ended up drowned in the Tigris. Another fact that Shafak rescues from media silence is the continued slavery of thousands of women who were sold on by ISIS to people in Turkey and elsewhere in the Middle East.

There are Rivers in the Sky is a book that is difficult to put down, it consumes you with its magic, insights and poetry. It is my first Shafak book but as soon as I finished I ordered another three.

* Relief depicting Ashurbanipal relaxing in his garden. The head of the Elamite king hangs from a tree on the far left. 645–635 BC.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 EcoSocialism Elections Europe Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War