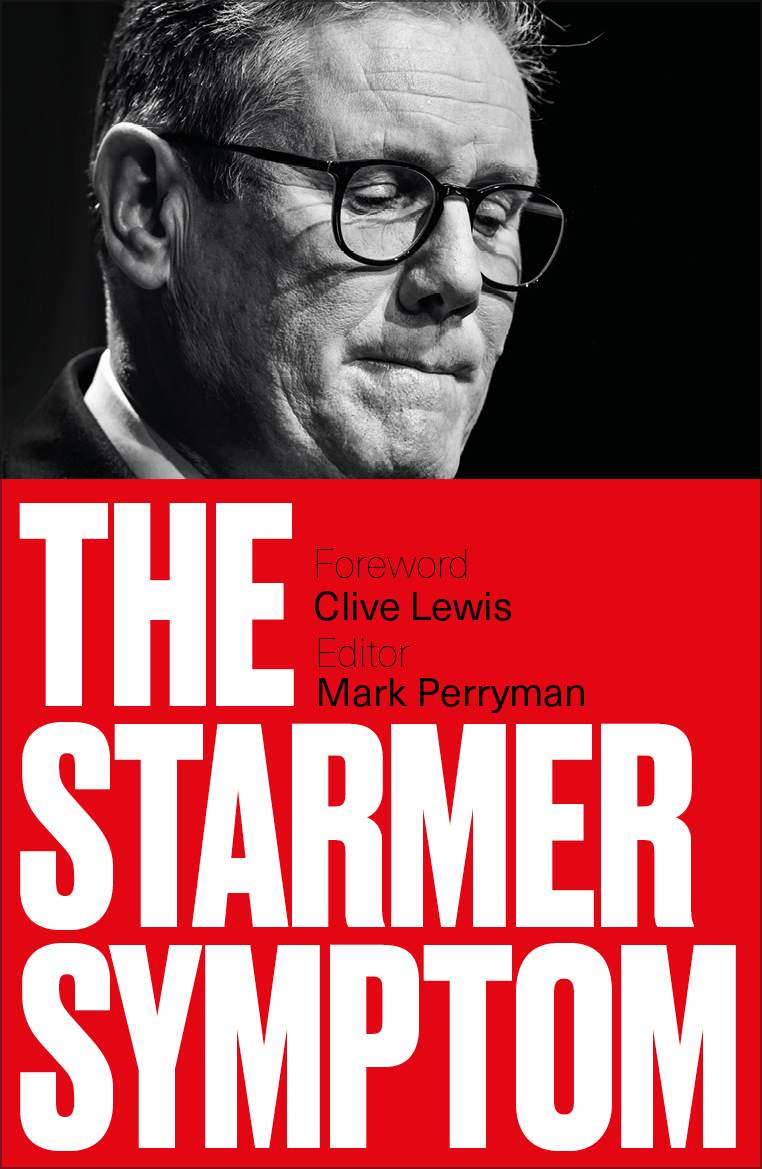

This is an Important book. It sets out a political analysis of the current situation by what you could call the ‘inside left’. Most, but not all the articles, are from people who are in the labour party and as far as I know none are members of a left Marxist group. They are not part of the ‘outside left’, the Marxist and Leninist groups who believe we need a new revolutionary party to bring about a break with capitalism.

Three of the contributions, including from the editor, Mark Perryman, and the foreword writer, Clive Lewis MP, are given by Labour party members supporting the recently formed Mainstream group which defines itself as radical realist. Most people would say it is a realignment of the soft left with some individuals who are (were?) more associated with the harder left Socialist Campaign Group (SCG). For example, Clive Lewis and Dawn Butler who had already been part of a New Left group which had differences with the SCG over foreign policy and the shortcomings of Corbynism.

It is important for people on either side of this left political spectrum to engage with the ideas of the other side. Unfortunately, much of the time the discussion takes place in two different silos.

Leaving our silos

Both the inside and outside left can agree about the anti-worker and even racist policies of the Starmer government, and the book captures a lot of that despite being published only a few months into the new government. Socialists from both sides are also involved together in campaigns protesting genocide in Gaza, attacks on disabled people and Labour’s retreat on saving the environment.

It is worth looking at the impact of the tactical and strategic choices of both groups since the book has been published. Those working inside Labour have seen a further reduction in the number of left activists – barely 15% of constituency delegates at Labour’s conference were identified by Momentum as ‘left’. Left candidates got around 10,000 votes in elections to the National Executive Committee. The unions helped get a positive Gaza motion through against the leadership, but that was about it.

On the other hand, this left is encouraged by the welfare cuts rebellion, the defeat of the Starmer candidate, Philippson, in the deputy leadership contest, the realignment/reawakening of the soft left around Mainstream/Tribune and the increasing chance of Starmer being challenged. To an extent, Neil Lawson’s chapter about reshuffling the left has been partially borne out. Much hope is invested in Andy Burnham, greater Manchester Mayor, as a leadership challenger who can turn the party back toward the left. Clive Lewis has just offered his Norwich seat to Andy. You wonder how much consultation Clive had with the local left or party members.

Your Party emerges

However, since the book was published we have seen the factionalised, rather top down formation of Your Party, headed up by Corbyn and Sultana. It drew over 800,000 online expressions of interest and already has over 50,000 members signed up. Hundreds of meetings at a local and regional level have drawn many more people than the Inside Left could mobilise. Alongside this you have had the Green surge to 150,000 members, attracted by the ecosocialist leadership of Zack Polanski.

Many of these new members are ex Labour members and activists. Hilary Wainwright in her contribution to the book picked up more than the others on this upsurge on the left outside Labour. However, since then some of the other contributors like Perryman, Clive Lewis and Jeremy Gilbert have been positive and non sectarian towards the new developments.

Nevertheless, the real political differences inside Your Party, which meant some activists switched to joining the Greens, shows that the outside left has not yet got its act together. There is no guarantee that it will win over the remaining socialists in Labour and begin to replace it any time soon. In fact the irresponsible actions at the top of Your Party has held back some Labour activists from jumping ship.

Consequently, whatever happens to Labour, either a more progressive reset post Starmer or further disintegration faced with the rise of the left and Reform, this group of socialists inside Labour can still make an important contribution. If a new socialist party is going to win them, and the trade unions, it is no use just denouncing the crimes of Starmer, telling them they are wasting their time and calling on them to join us.

Those of us committed to a clear break with capitalism based on the self organisation of the working class must understand the thinking of those still sticking with Labour and engage in serious political discussion with them. Building something that, as Mark has said, ‘blows up’ the limits of Labourism, will require all of us to engage, act and discuss.

Mark’s book is a contribution to this vital task insofar as it lays out the framework within which the inside left sees politics.

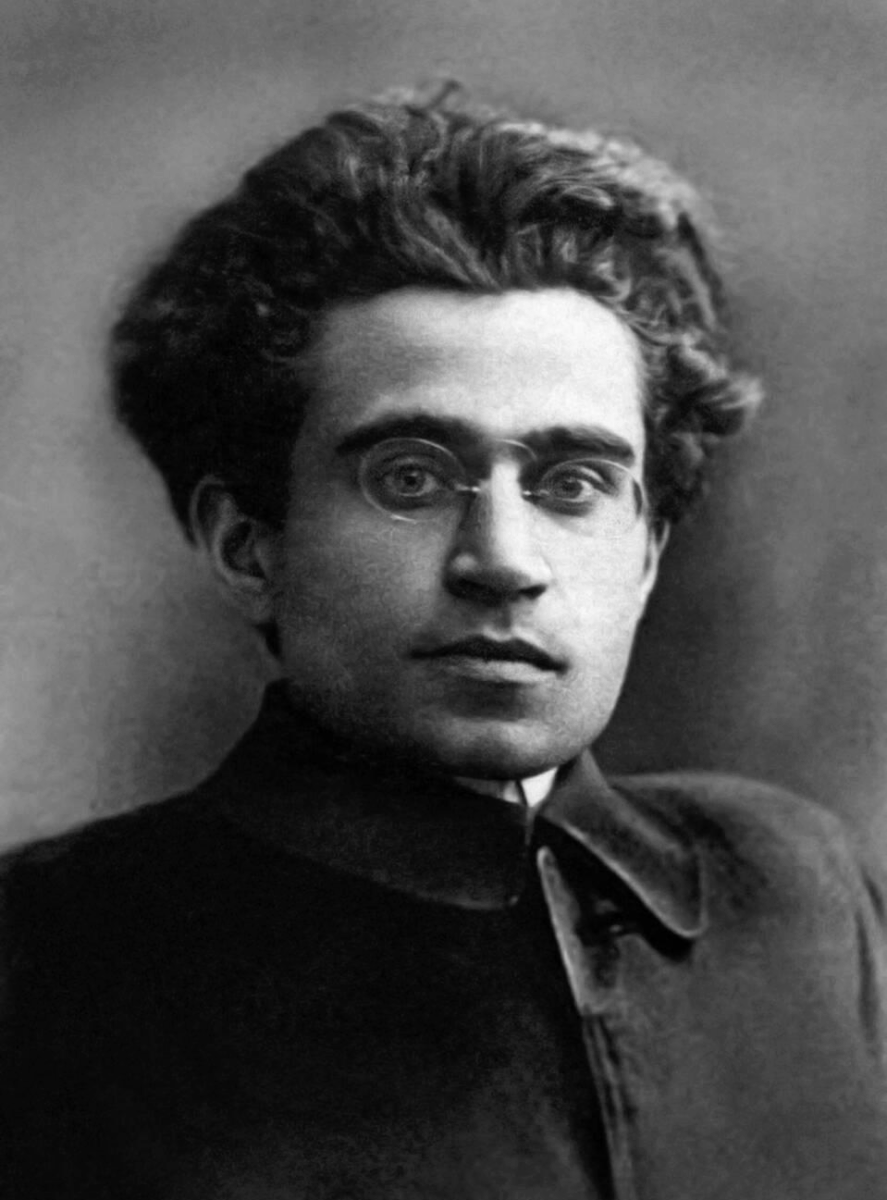

Using Gramsci

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear

Antonio Gramsci

The editor has used the well known quotation from Antonio Gramsci as a hook to analyse Starmer’s government. Some of his other ideas, such as the counter hegemonic bloc, are implicitly taken up by himself and others in formulating a strategy for the left. But some of our readers may know little about Gramsci. Who was he?

He was a revolutionary Marxist who was a leader of the Turin workers councils following the First World War. He was a founder of the Italian Communist Party but later jailed by Mussolini in 1926. Released in 1936, he died a year later as a result of illness aggravated by incarceration. Although cut off from active politics in prison, he wrote perceptively about the issue of the revolutionary party winning support in a quite different type of capitalist society from Russia in 1917.

In Europe there were developed democratic institutions, a large organised working class with roots in these institutions and a civil society distinct from Tsarist Russia. Hence the need to recognise the capitalist state ruled through constructing consent as much as armed force.

Other key ideas were how to develop a counter hegemonic bloc to that of the state, how to develop organic intellectuals as the backbone of the party and the difference between a war of movement (to seize state power) and the war of position (to develop a counter hegemony over a period of time). Given we have not seen a successful revolution in a more advanced capitalist society his ideas are relevant.

Perryman correctly identifies today’s symptoms like Gramsci did as both extremely negative to the working class – the surge of racism and success of Farage – and potentially positive where we see new radicalisation of an entire generation over Palestine. For Gramsci living under a fascist regime, the morbid symptoms included state violence and so socialists had to be prepared to organise to respond outside parliament and to build its own armed capacity to confront and break the power of the state. Eventually his comrades played a big role in building the Italian resistance which drove the Nazis out of the north of Italy before the Allied armies arrived.

A counter hegemonic bloc, conceived in purely ideological terms without a political understanding of confronting the state and responding to its inevitable violence when challenged, would be only half a strategy. Gramsci Never renounced the need for a revolutionary party (the Modern Prince in his notebooks) to be built as an alternative to the institutionalised reformist parties. He did not see a network of social movements, campaigns or unions as sufficient to bring about an anti-capitalist revolution.

Fergal Sharkey, former Undertones singer, has been magnificent in building a campaign against the water company profiteers and polluters. He helps radicalise people but he is not a person who is building a political, eco-socialist alternative that can challenge the state and capital in a strategic sense.

Starmer’s symptoms

Clive Lewis in a foreword critical of Labourism and its current managerial/technocratic form outlines five symptoms of Starmerism:

- Ideological ambiguity

- Technocratic managerialism

- Corporate influence

- Aversion to pluralism

- Political timidity in relation to the existential threat to planet earth

Like Perryman in his article he shows how today’s Labour has evolved from traditional social democratic politics made possible in the post-war boom, when the capitalists could afford to increase wages and social spending. Even the personnel have changed. Labour candidates today come much more from a corporate or consultancy background than the public sector, let alone from the working class or trade unions. Gilbert goes into detail about this is his chapter. Today it is better perhaps to use the term social liberal to describe Labour than Labourist or social democratic.

His point on pluralism is more problematic. Starmer’s onslaught on Labour as a broad church has gone much further than even in Blair’s day. All socialists would support the right for all shades of left opinion to be allowed to flourish in Labour. However, more debate on its own does not change much if the left is so weak it has no chance of winning policy or candidates. You get the impression sometimes from people sticking with Labour that if only the leaders listened to our great ideas we could convince them.

You hear people saying we have won the policy argument but without controlling the party it is all just talk, like passing conference resolutions that Starmer ignores. Corbyn was so viciously attacked because for a while he aligned policy with the leadership, although not with the apparatus and the PLP. The reason so many people have left Labour is precisely because that democratic life barely exists today.

Still, Lewis (and Perryman) also support pluralism in the sense of forming coalitions with the Liberal Democrats – who have never been anti-capitalist or even anti-neo-liberal. True, they justify this on the basis of the anti-democratic scandal of our first past the post system which means for Labour voters in places like Lewes in rural Sussex it is difficult to remove the Tory MP by voting Labour. They have always correctly championed the cause of proportional representation – as opposed to the shameful lack of campaigning or even opposition of many on the more radical left.

Electoral coalitions with the Liberal Democrats?

While electoral deals with groups to your left (such as with the Greens today) will not dilute pro-working class policies, any alliance with the Liberal Democrats would mean concessions and reinforce a neo-liberal party that does not defend working class interests. There was a de facto electoral deal with the Liberal Democrats at the last general election. As the article by Paula Surridge in this book explains, this was a significant factor in the Tories defeat.

Yes it helped defeat the Tories but it has also boosted the Liberal Democrats who will be an opponent of any future Labour government trying to implement some of the radical policies proposed by contributors to this book. Would a Liberal Democrat party have agreed to this nod and a wink deal if the Labour Party had run on the 2017 manifesto? It would be a mistake today to say the main task of the left is to form a popular front including the Liberal Democrats to block a possible Reform or Reform/Tory government at the 2029 general election.

The rise of the Greens, left independents/Your Party and even Reform mean this sort of pluralism makes less sense. A huge mass of non-voters could still be mobilised with a radical ecosocialist programme. Certainly there is nowhere in Gramsci where he argues for a historic compromise with the bourgeoisie. Indeed the Italian Eurocommunist CP did precisely that, twisting Gramsci’s thought to justify it. This party has effectively dissolved itself into another social liberal party.

If the Liberal Democrats as a party or as individuals want to support campaigns against genocide in Gaza, against Labour’s attack on refugees or against racist/fascist marches we should welcome them. The same goes for organizing local poltical events that Mark helps organise in Lewes. As he says all should be welcome, just bring an open mind.

Positive symptoms

Clive Lewis recognises symptoms showing there is hope for the future in terms of:

community organisers, the cooperative movement, union branches, citizen assemblies, environmental campaigns participatory budgets, union fights in Amazon and for delivery riders

This is rather like left groups such as Socialist Worker, which sees rising anger and struggle everywhere. However, such a perspective is a little one dimensional and exaggerated in spite of well intentioned sentiments. These struggles and institutions of the movement operate in a political context which at the moment is still dominated by creeping fascism and a shift to the right. These fragmented examples need a political instrument, a tool that can unify and politicise their struggles.

The question is whether even a rejuvenated Labour left presumably led by the radical realists of Mainstream or Burnham can push Labour to become such an instrument. An approach that remains primarily focussed on getting people like Powell , Burnham or left candidates selected appears too moderate and too electoralist – which is the very problem identified by most writers in this book.

Also these parts of the movement commended by Lewis can have a variety of political approaches some of which are not particularly a threat to capital or its state. This is the case for the Preston model or community wealth building. Nobody opposes using local councils to refuse outsourcing and to work better with the community or use smaller local businesses, but is the link being made to an overall socialist alternative?

BAE systems still dominates the Preston hinterland and plays a role in the arms industry, can the Preston model lauded by Lewis have any impact on BAE? How effective have such types of initiative been in trying to stop Starmer’s austerity, armaments’ drive or repressive measures against protest or migrants? Lots of community projects do good things and get people involved but can seem to operate in their own bubble detached from the determinant national class battles.

A response to the book’s contributors

The book is divided into 4 sections. There is no space here to go into a detailed reaction to each contributor. Here we will make some brief comments on each chapter:

- Mapping the hope –

This section includes a useful reference with data on how Labour won the 2024 election by Paula Surridge. Most people on the left would agree with her analysis which shows Labour’s loveless landside was mostly about the Tories losing than any great master strategy or wave of enthusiasm for Labour.

Jeremy Gilbert shows how Labour’s politicians are integrated into a corporate world. He is clear on how the war against Corbyn was not just about personal enmity but based on the material interests of a bureaucratic layer that feared for their jobs and status. He identifies how the Labour leadership represents a residual technocratic ruling class fraction that manages existing capitalism. It does not have a worked out political ideology distinct from traditional Labourism or Faragism. He is good on how Blue Labour distorts reality about the white working class and is adapting to reactionary ideas about some innate ideology or identity it “should” possess.

One of the stand-out pieces I enjoyed was by Gargi Bhattacharyya. She correctly shows how Labour openly presents itself as constrained by myths of economic growth and the limits of the market. It can only manage the reality that capitalism defines. She also passionately identifies the continuity of racism and colonialism at the heart of Labourism and is highly relevant to the latest policies of Shabana Mahmood who is aping Reform policies on migrants and refugees. It is worth quoting her final paragraph:

Yet now we can see a government adamant that no aspiration of the population can be met and at the state can do little to nothing . The only exception is to amplify acts of state racism presented as extensions of the popular will. If such promises of racist excess fall short, the underlying anti-politics of the non-claims of government can be recirculated – hating experts, hating lawyers, hating due process, hating refugees, hating Muslims, hating black people. This is a government that presents itself as embodying the inadequacy of the state, and therefore relies on a repeated whipping up of hatred as an energy that substitutes for consent. I curse them with the core of my being.

Joe Kennedy in his article, Son of a toolmaker, expertly deconstructs what he dubs the fake authentocracy that leverages false claims about class against the left. It describes but really proscribes – “laying bare the real but serves up what has been conventionalised in advance as realistic.” A bit like the rubbish of reality TV programmes.

2. Fall out – how party politics is being reconfigured.

Neal Lawson lays out the background to the recent formation of Mainstream which we have already discussed above. He states that:

Corbynism has largely come and gone without leaving a trace.

The Corbyn project had it faults – mainly a strategic failure to understand how the labour bureaucracy would react to it and incoherence over Brexit – but to say it left no trace is unfair. The huge numbers of activists around the Greens and Your Party are living evidence that the project has a legacy. His article tries to identify a third way or space between Starmerism and the Greens/YP/Marxist left – maybe we could call it the Burnham beach. He even includes Liberal Democrats in this space as well as think tanks and academics.

Bernstein argued against the revolutionary politics of Rosa Luxemburg in the early 20th century. Like Lawson he focused largely on the means and disconnects them from the ends. The perspective of a radical rupture with capitalism and its state disappears in favour of a process within the institutions, albeit supplemented by popular participation. The ‘hard’ left is lumped with the far right as only worrying about the ends in politics.

I hope he will work with the new forces outside Labour, but Lawson seems to be in another place. We can support some of the same policies he is outlining but there is an absence of a realistic strategy that accounts for class struggle and state power. There is the delusion – since contradicted in reality – that we could not rule out a Starmer pivot to the left and he places his hopes in the record number of progressive MPs elected in 2024, which is an exaggeration.

The chapter on the Conservative meltdown by Burton-Cartledge is a good account of the possible terminal crisis of the Tories and Joe Mulhall gives a useful description of the rise of Reform.

Hilary Wainwright makes a case for an independent left and acknowledges a legacy inCorbynism while correctly criticising that project for not organising more resilient extra-parliamentary sources of counter power. She shows how the practical and tacit knowledge of organised workers in struggle is crucial for challenging the dominance of the free market.

While accepting that previous attempts to organise independent parties like Respect failed, she expresses hope that “horizontal organisation as much as national initiatives will result in a genuinely independent party with a powerful , transformative popular base”. Despite troubles with Your Party, it looks likes a new party, starting a membership comparable that of the CP in its pomp after the Second War, is going to be created. In this sense her analysis has been borne out.

3. Change Stability and Contradictions

Danny Dorling takes head on the myth peddled by Labour that capitalist growth will reduce inequality and armed with facts and figures, completely demolishes it. He makes a useful distinction between wealth inequality (assets) and income inequality, so for instance France or Germany has less income inequality but more wealth inequality. Scotland under the SNP has reduced income inequality more that England. Inequality produces negative effects that also hurt those who are not poor. It is convenient for our rulers too that inequality lowers turnout in elections.

James Meadway, an economist who since the book was written has joined the Greens, shows how adherence to the fiscal rules has meant that even some of the half decent policies like the green energy plan have been cut back.

Jess Garland deals with a topic often ignored by the Marxist left – the need to make deep going democratic changes to our archaic systems. She makes all the arguments for proportional representation but implies this is a recipe for more moderate policies, less volatility and better decision making. Her praise of consensus does not really operate where class struggle is alive and well; there must be confrontation if we are going to make meaningful change.

Finally Andrew Simms speaks out on the need for an ecosocialist approach – a stance often neglected by both inside and outside lefts.

4. Outcomes

Emma Burnell in her contribution critiquing Labour according to McSweeney suggests both the chief of staff and the Corbyn people suffer from the same tunnel vision. They share a tribal culture and the party should modernise, professionalise and de-factionalise. Starmer’s assault on the left is described as ‘clunkiness’. Frankly I thought this was fairly uncritical and not really very helpful in sketching outcomes.

Gregor Gall deals with the role of the unions in any left project. He is right to criticise the limits of the 2022 strike wave and he identifies the difficulties of developing a strategy that will involve them in a socialist prolect.

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown backs up the points made powerfully by Bhattaharyya about racism at the heart of Labourism and she also talks a lot more about Gaza. Today she continues to take on Labour about Gaza and its racist attacks on migrants and refugees from the pages of the I paper.

This section ends with a contribution that reflects the strategic weakness of the book despite an overall good analysis of the symptoms. Eunice Goes is more positive to Starmer than anyone else. She distinguishes between Labourism and Social Democracy too sharply since Labourism is one of Social Democracy’s forms. Then she even speculates that Starmer has social democratic possibilities! If she was wrong about that then she has been proven even more wrong since. No surprise that there is no mention of Gaza or migrants in her article.

Testing the limits of Labourism

Some points Perrryman makes in his keynote essay, for example on alliances with the Liberal Democrats, working inside Labour or on community wealth building, have already been dealt with. We will limit ourselves he to some brief concluding comments.

He gives us an historical account of how Stuart Hall in the 1980s understood Thatcherism as a ruling class hegemonic project more quickly and often with more nuance than the outside left. He is right to say Gramsci’s concepts helped him present such an analysis. To fight back we did not just need to organise and support struggles like the Miners but to develop a counter-hegemonic bloc that could respond to Thatcher’s ideological offensive of individualism, entrepreneurship and nationalism.

There were some reformist versions of this bloc that ‘over ideologised’ the process and downplayed the role of material interests such as selling council houses – working people did not have to agree with any ideology to know this was a good deal for them. The repressive role of the state that we saw was crucial in her winning the miners’ strike was also downplayed.

Perryman is right that socialists should not scoff at what the park runs, the food banks or other community initiatives represent. A little like the pre-figurative actions that Hilary Wainwright identifies as incubators of a possible socialist future. Alan Gibbons, who we can consider part of the outside left is an independent left councillor in Liverpool and he regularly organises litter picks in his area. Revolutionaries need to get their hands dirty in this sort of work if we are going to win mass support.

Working together on the Left

Let’s finish the discussion with thoughts from Jeremy Gilbert who contributed to the book. He wrote an article in Tribune last week that recognises the new realities of the political situation. He writes how there are three or four possible future scenarios:

- a popular front led government linking a soft left Labour party to the Liberal Democrats and including the Greens and other left parties

- a popular front hegemonised by the Greens

- Your Party could emerge as the major force

- a vanguard party will lead in a deep crisis of representative democracy

He suggests we keep these possibilities open while supporting each other in doing so. Gilbert has an open non sectarian attitude towards parties to the left of Labour:

There are perfectly good reasons to assume that the right-wing bureaucracy currently controlling Labour will prove impossible to dislodge, at least without external as well as internal pressure, and that such external pressure could only be applied by parties to the left of Labour

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 EcoSocialism Elections Europe Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War

I welcome Dave’s article. We do indeed need to talk about the Labour Party and I would like to contribute to the discussion. This will take time however. Dave’s article is 4,295 words, and then there is Mark Ps book to obtain and read. It will not be this side of the Christmas holiday.